Hello there! 2023 is about to end soon, so it's a good time to sit and reflect on it. If we think about the tech industry, in general, it's easy to define which topic was the hottest this year - AI. And the chances are that in 2024, this area will grow even bigger alongside the growing investments and the new astonishing scientific discoveries in this field.

Unlike previous "big things" in tech, like blockchain, crypto, NFT, Web3, etc., AI is way more accessible and covers more use cases than the rest:

I can guess with a high probability that you have already embedded some of the AI tools in your daily life or career-related activities

the chances are that the backlog of your project(s) has/had quite a few tasks related to introducing/integrating AI capabilities, and some of them are pretty damn good features!

If you answer "no" to these bullet points, you are missing out a lot, my friend. In my case, I'm actively using GitHub Copilot for coding assistance and ChatGPT for brainstorming ideas. I believe this list is very familiar to my fellow software engineers out there, and it's not only me who experienced a significant productivity boost thanks to these tools.

Of course, we will see what will happen with AI development once the hype is gone (and some investments with it) and there is a new "big thing" out there, like quantum computing or something less useful/practical. But for me, personally, the tools I started to use in 2023 are here to stay, as now they are a part of the essential toolset alongside Git, Docker, Excel/Google Spreadsheets, note-taking apps, etc.

As you can see, I'm pretty happy about the possibilities AI brought to us this year. And many articles out there talking about the cool features those tools have and the game-changing UX they bring. Sometimes, they create a feeling that those are silver bullets. However, it's not common for those posts to explore the problems, limits, and challenges of those tools. "Know your tool!" - someone wise once said. That's why today we are going to discuss some of these "dark parts" of the AI tools we use to be aware.

A short disclaimer: the message of this post is not "don't use the AI tools," but instead "use the AI tools mindfully." - the author is not one of the Luddites, I can assure you =)

Contextless advises

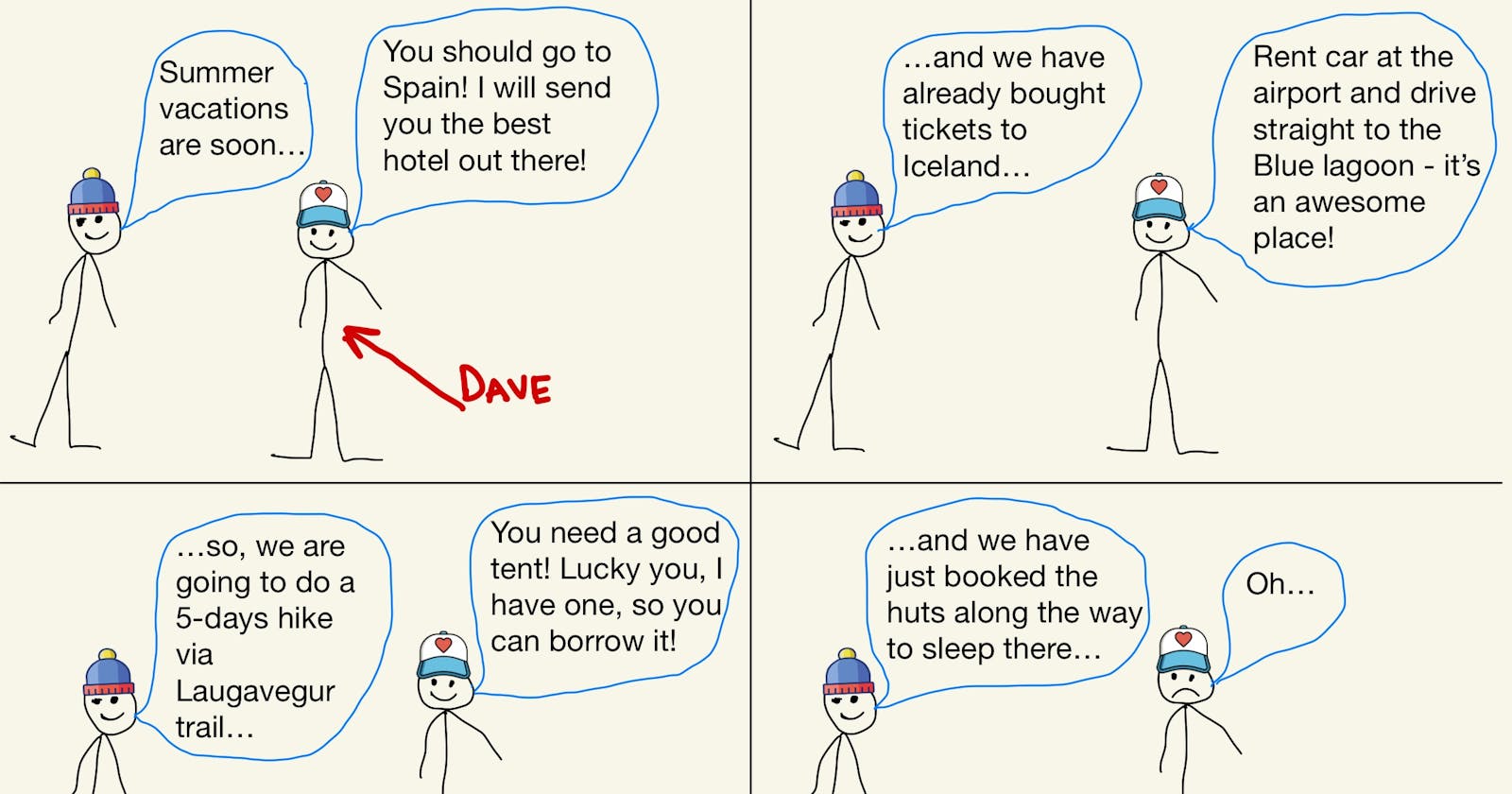

Let me introduce you to Dave. Dave is a friendly and very talkative guy, the social bee, if you will. But you should know this about him: Dave likes to share his opinions and, even more, give his advice regarding whether he has been asked to or not. Usually, he doesn't bother diving deep into your situation, but instead, he prefers to share his thoughts right away: "Do you want to buy a car? Buy Tesla!", "Are you considering upgrading your laptop? MacBook Pro is all you need, I assure you!". Here is him:

Do you have any Dave-s in your life? I wouldn't be surprised if you do.

As you can see from Dave's answers, he is not a bad guy, he really wants to help, and his advice is not dumb, but it's not something we should rely upon, at least at the very beginning of the conversation.

Why did I mention Dave at all? The post was supposed to be about AI tools. Well, let me tell you that GitHub Copilot is one of the "Dave-s", especially once you have created a new project. It's easy to reproduce this behavior as of the day of writing this post:

open your favorite IDE (I use IntelliJ IDEA from JetBrains)

create a new project

create a new file "test.md" there

open it and start typing "My name is "

Not sure about you, but in my case, I got this suggestion from GitHub Copilot:

Ok, let's accept the suggestion and add and I'm from - I got this:

Hey, wait, but it's not a code! I hear you, let's try the same with a code:

create a

main.gofile in the root of your projectmake sure it has the

package mainon toptype/copy-paste this

func pickLast() string {and wait for the suggestion

I got this on my machine:

It's a fair suggestion, and it compiles, but is this something you, as a software engineer, would suggest? Would you suggest anything at this moment of project development if, let's say, you are assisting your colleague via the pair programming session, but you knew nothing about this project before now? It's a rhetorical question.

What should we do about it?

Well, the same as with Dave, we should be aware of this way of working with GitHub Copilot and be careful with the suggestions it provides at the very early stage of the project or before its model has enough time and data to learn about your project.

Also, I'd recommend enabling native IDE suggestions alongside the GitHub Copilot ones to get the best of the 2 worlds: AI-based and docs/code-based, meaning that the latter doesn't suffer from hallucinations. You can do that:

in JetBrains IDEs by:

Settings->Languages & Frameworks->GitHub Copilot-> enableShow IDE completions side-by-sideoption under theEditorsettings chapter

Once enabled, it works like this:

I'm not a heavy VS Code/Vim/Neovim user, that's why I'm not sure how to achieve the same there - if you know, please, let me and others know in the comments section - pay it forward =)

XY problem

Have you ever heard of XY problem? If not, here is how Wikipedia defines it:

The XY problem is a communication problem encountered in help desk, technical support, software engineering, or customer service situations where the question is about an end user's attempted solution (X) rather than the root problem itself (Y or Why?).

The XY problem obscures the real issues and may even introduce secondary problems that lead to miscommunication, resource mismanagement, and sub-par solutions. The solution for the support personnel is to ask probing questions as to why the information is needed in order to identify the root problem Y and redirect the end user away from an unproductive path of inquiry.

If that doesn't make sense, here is a good example from "The XY Problem" website:

<bob> How can I echo the last three characters in a filename?

<feline> If they're in a variable: echo ${foo: -3}

<feline> Why 3 characters? What do you REALLY want?

<feline> Do you want the extension?

<bob> Yes.

<feline> There's no guarantee that every filename will have a three-letter extension,

<feline> so blindly grabbing three characters does not solve the problem.

<feline> echo ${foo##*.}

As you can see from this example, the person who answers the question should have a certain level of both professionalism and soft skills to get to the root of the challenge the other person is facing. That's not an easy task, I have to admit!

What about our AI friends? Lately, I have been brainstorming an idea for creating a tool that will:

fetch a list of GitHub projects within different organizations I have access to

do specific manipulations within the

package.jsonof each repo

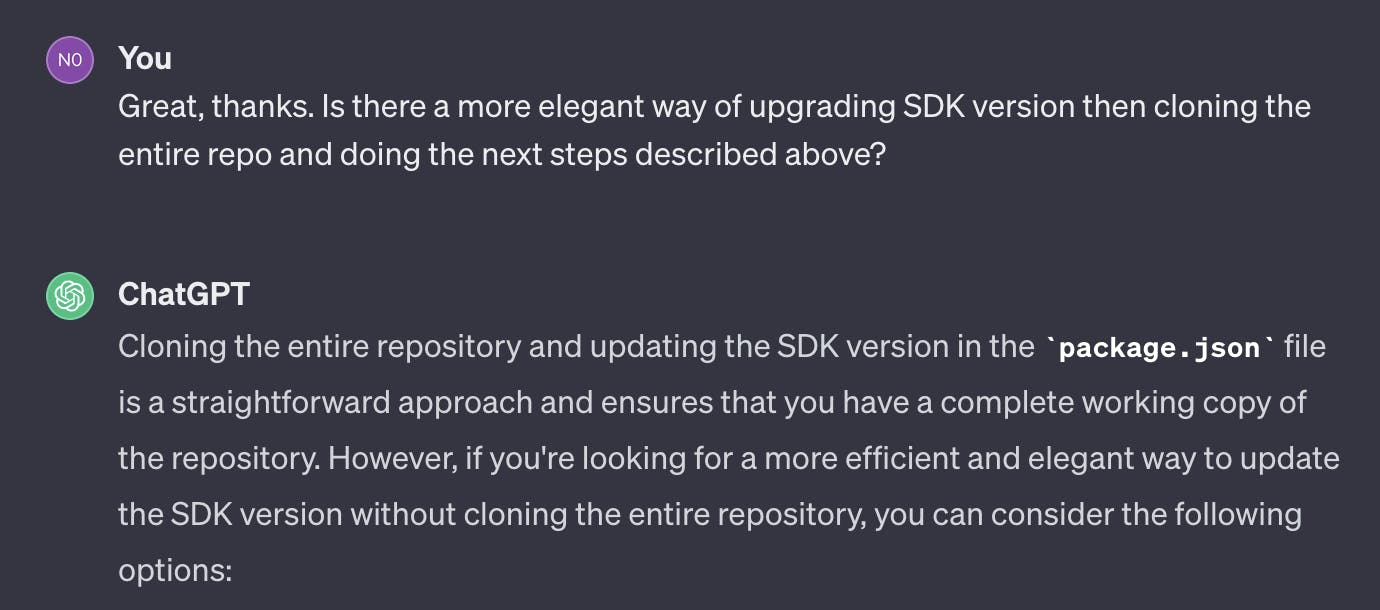

And I used ChatGPT to be my buddy in that process. I provided a high-level context for the tool and said that I'm considering writing a script that will clone each of these repositories, read the content of the package.json file via the IO operation, make the desired change, and write the modified context back to the file. My AI friend replied that it was a good idea and explained how to do that with some pseudocode. However, I felt that I was reinventing the wheel with all of that, so I decided to double-check:

and then ChatGPT suggested a list of alternative approaches, one of which was to use the existing GET /repos/:owner/:repo/contents/:path endpoint of the GitHub API. That was good advice and exactly the way I went forward (successfully if you are wondering). But would I have gotten it if I hadn't explicitly asked about more elegant ways of achieving the desired result? Nope.

What should we do about it?

That's something that I'd like you to be aware of while using tools like ChatGPT: they are falling (still?) into the XY problem, so be mindful and explicitly double-check whether the way you are going right now is the best one and whether there are any better alternatives.

The code that looks damn realistic but has some hard-to-notice issues

Some time ago, I was working on my simple terminal reminder app remindme (btw, check it out, it's pretty good and might be useful for you, and it's FOSS), and it was one of the first times when I could feel the power of the GitHub Copilot assistance: it basically wrote all of the SQL-related code in my project. And I have to say that the queries were pretty good: here is what one of the functions looked like:

func (repo *sqliteReminderRepo) List() ([]common.Reminder, error) {

rows, err := repo.db.Query(`

SELECT id, message, remind_at FROM reminders;

`)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

reminders := make([]common.Reminder, 0)

for rows.Next() {

var id int64

var message string

var remindAt int64

err := rows.Scan(&id, &message, &remindAt)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

reminders = append(reminders, common.Reminder{

ID: id,

Message: message,

RemindAt: time.Unix(remindAt, 0),

})

}

return reminders, nil

}

It's a decent code, but there is one catch that is easy to miss while doing a code review, especially if the pull request is quite big: a rows variable created in line 2 of the code is of type *sql.Rows. And it should be closed to release the resources once the processing is completed, that's why we need to add defer rows.Close() after the 1st if err != nil { ... } statement like this:

func (repo *sqliteReminderRepo) List() ([]common.Reminder, error) {

rows, err := repo.db.Query(`

SELECT id, message, remind_at FROM reminders;

`)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

defer rows.Close()

reminders := make([]common.Reminder, 0)

for rows.Next() {

var id int64

var message string

var remindAt int64

err := rows.Scan(&id, &message, &remindAt)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

reminders = append(reminders, common.Reminder{

ID: id,

Message: message,

RemindAt: time.Unix(remindAt, 0),

})

}

return reminders, nil

}

In this case, leaving rows open won't cause huge problems because the app is small and is not exposed to the big scale. However, not closing resources (especially the IO or network ones) in the production code can lead to severe issues and wake the on-call fellas up in the middle of the night.

I believe you'll agree that it's easier to miss this line while reading the code written by someone (the colleague or AI assistant) than to make the same mistake while writing this function manually.

Let me show the same "realistic but not entirely correct code" problem but from a different angle. Some time ago, a company that I was collaborating with got a new junior engineer - let's call them Knut. It was the guy's first job ever, and I heard from the other colleagues (who worked full-time on the same project as Knut) that the new hire was doing great.

Some weeks later, I got an email that Knut requested my review of their pull request. I opened the link and saw Files changed 70 . "Wow!" was my first reaction, and then I grabbed a cup of coffee and decided to allocate an hour or so to do a deep review. I left a bunch of comments, nothing biggie, but there was one moment I couldn't comprehend: I noticed that Knut introduced a new dependency by adding a pretty big library (one of those "Chuck Norris" tools that can do everything). I briefly went through the list of code changes one more time, but I couldn't see where this library was used. I left a comment about that change as well, and on top of that, I sent a private message to Knut and said that if there is a need to jump into the call to clarify some of the comments or explain some code-/domain-wise moments, I could help with that.

Pretty soon, we jumped into the call and had a good discussion on the places to improve within the PR. Finally, I had an opportunity to ask about that new dependency introduced by the pull request. Knut explained that otherwise, the project wouldn't compile, so the guy asked ChatGPT about how to fix those errors, and that's the solution the tool suggested using. And it helped!

Let me step aside for a moment here to share some context. Suppose you have experience with the Java language and a Spring framework. In that case, you might be familiar with the situation when there is a library, something-cool-for-web, that, for example, brings you a bunch of tools for web development, but it might provide only the interface for some parts, like HTTP Client. And now, it's up to you to provide the implementation or the explicit dependency for the HTTP Client to make the tool work. Otherwise, the compiler won't be happy, as the interface without the implementation is not a way to go.

So, the correct solution is to use the some-cool-and-tiny-http-client library and provide the missing implementation to the something-cool-for-web configs. Instead, ChatGPT suggested using the huge-and-heavy-all-inclusive library, which has our some-cool-and-tiny-http-client within its sub-dependencies but also hundreds of others on top. Yes, this approach fixed the issue and made the compiler happy, but do we need those 100+ new libraries within the project? Of course not, as it creates a lot of risks, from unexpected bugs/behaviors to security vulnerabilities. But it was easy to miss this part while doing a code review of the pull request with 70 files changed.

Don't get me wrong, the pre-AI tools we used (and still use), like StackOverflow, are also exposed to the same issue, but that doesn't mean we shouldn't mention it then.

What should we do about it?

As with other AI hallucinations, we should be extra careful with all the output provided by those tools and do our best to verify it. In the examples above, I mentioned only the manual verifications, but it's a good practice to rely on the automation tools as well, like different kinds of tests (unit, integration, end-to-end, etc.), linters, dependency restrictions, pro-commit hooks, code-formatters, etc.

On top of that, we should aim to introduce/advocate a practice of smaller PRs (whenever possible) to make it easier to review and increase the chances of finding issues, if any.

And my personal reflection: since AI assistants are getting pretty good at writing code, we should invest more time and effort into the skill of reading/reviewing code, as it becomes more and more important these days.

The sunk cost fallacy

This one is not a problem of the AI tools, but rather of us humans. And it's the most questionable point of this post, so please feel free to disagree. But let me explain first what I mean here.

According to this article on Scribbr:

The sunk cost fallacy is the tendency for people to continue an endeavor or course of action even when abandoning it would be more beneficial. Because we have invested our time, energy, or other resources, we feel that it would all have been for nothing if we quit.

Sunk cost fallacy example You are watching a movie, and after 30 minutes you realize it’s not what you expected. Instead of finding another movie, you convince yourself to continue. You think to yourself that you have already invested half an hour and the whole movie is just an hour and a half. If you quit now, you will have wasted your time, so you decide to stick it out.

I'm not sure about you, but it's something that has happened to me. Here is one of the examples in the scope of the AI tools.

These days, whenever I have time, I work on my new FOSS pet project: a service to ping your APIs/websites that is configurable via a simple YAML file and should support various queries/selectors (CSS, jq, etc.) and different protocols (HTTP(S), TCP, UDP, GRPS, GraphQL, etc.). One of the most challenging (and boring, IMHO) parts was to define the structure of the YAML config file, as it feels like creating a new DSL, so it's essential to keep it simple, extendable, and as short as possible. For that reason, I postponed the YAML part until the stage when I created a skeleton for the business logic and implemented a happy path for one of the protocols (HTTP). Once the time came, I decided to create a YAML config example with all the possible options before making the specifications and schema.

I started with the first lines like these (pingheim is the name of the tool):

pingheim: 0.0.1

description: A sample of a full YAML file

pings:

To my great surprise, GitHub Copilot immediately offered me a completion that created the structure of the ping with the desired feature I had introduced in my business logic. I was quite happy about it, as it seemed like I could outsource the most boring part to my AI friend. So I accepted all the suggestions (there were dozens of lines of YAML code), quickly implemented the code of deserialization of this file, plugged it into the existing business logic, and decided to call it a day.

I didn't have time to get back to this project for the next couple of days, and when I finally could, I opened my IDE and saw the generated YAML configurations with a fresh look. Well, it was clear that while there were a lot of valid points and even interesting ideas I had foreseen, the result itself was definitely far from being perfect and production-ready. What's worse is that it required proper surgery rather than a few minor changes to make it the way it should be, considering the abovementioned requirements. Did I mention that I found this part boring? Well, that was the moment when my inner resistance struck the most: "Come on, man, it's not that bad!", "It will require changing the entire codebase if we modify this part", "Let's keep it for now and change it in the future", "It's a tool for your own purposes, why bother?", "You invested so much time and effort to go back and reiterate!" and so on and so forth.

As you can see, I became a victim of the sunk cost fallacy. I even had to interrupt the coding session and go for a short walk to fix the frustration part. At the end of the day, I made the right choice and spent another couple of evenings changing everything the way it should be, but that was mentally hard to start/keep doing. Otherwise, my tool won't be the one I wanted to build, but rather the one that generated code pointed me to.

Again, it's not a problem of the AI tool, but rather my problem of non-ideal human-being - according to the fact that such effect has a separate term and About 1,920,000 results in Google search, I'm not alone here. The thing is that AI tools can help create the feeling of a massive investment by generating tons of code that is not that easy to refactor once accepted as it is. In the pre-AI era, the same situations could have happened if folks were copy-pasting large chunks of code from StackOverflow or similar places, but AI helps make it faster and in larger volumes.

While doing a couple of pair programming sessions with other engineers of different levels (from intern to staff), I realized that I'm definitely not alone there: some people are being caught in the same trap I mentioned above, and then it's up to their level of discipline and professionalism whether they can overcome it. Have you ever seen/experienced something similar?

What should we do about it?

The answer is simple to define but sometimes hard to follow: be aware of such cognitive bias and always remain professional and disciplined. If you feel tired, call it a day or go for a short walk/physical activity to let the brain relax, as it's way easier to be hooked by this bias once you are tired, and, therefore, you might be considering shortcuts to finish the task.

Privacy and Legal

This is the most boring and overlooked (by us engineers) challenge AI tools introduce: privacy and legal compliance. I remember that as soon as GitHub Copilot was released (in Beta?) for individual users, some of my friends and colleagues got access to it and started using it both for their pet projects and at work. It's only another tool, right? Well, it's not that simple.

There is an interesting discussion about "Is Github Copilot safe privacy wise?" on GitHub. The short conclusion is that it's not, meaning that you should not use your individual license with a code that belongs to the company, as the tool collects metrics, telemetry, and, probably, some code/suggestions/prompts as well. I can see that the same conclusion came from the privacy and legal teams of the different tech companies out there, so the company started the enterprise agreements' negotiations with GitHub to obtain the business licenses instead, which are more privacy-friendly.

For example, here is what GitHub states in the "About GitHub Copilot Individual" article:

As you can see, they are pretty transparent about the telemetry they collect from the individual users, but not for the business ones.

Many companies applied similar restrictions for the use of ChatGPT. The same approach goes for the other AI tools out there.

What should we do about it?

If you are using your private license with the production data, stop it right away! Talk to the lawyers in your company before sharing any company-owned data with the AI tools. Treat no approval as forbidden. We didn't share the company code on the internet forums and other services like StackOverflow, so we should treat AI tools the same way.

Final words

I know there are other issues and challenges with the tools we discussed above, especially related to the current AI limitations, but I am no expert in this field, so I'd like to let scientists discuss this.

I hope this post has triggered some thoughts, and it's more than OK to disagree with some. or all the points above (except the last one, as it's a law) - I'm open to meaningful discussion. As I said at the beginning of the article, there is no message to stop using these tools, but rather to be aware of their limits and use them in a better and more productive way.

As usual, if you liked my post and don’t want to miss out on my future publications, consider subscribing to my newsletter to stay tuned and get my new posts delivered right to your email inbox.

Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year to those who celebrate. See you in 2024!

Have fun =)